News & Commentary

Predictable Tuition Costs Would Help Families and Universities Plan for the Future

As any parent with teenagers knows, paying for college is hard and the nagging worry of “do I have enough saved” fuels many sleepless nights. Recently, there has been heightened public dialogue about the price of public higher education and some states are exploring alternative tuition policies, including free college. However, what has not been as present in these discussions is the stop-start nature of tuition increases and how this volatility has negative effects for students and families. For families, being able to predict the cost of not just the freshman year of college but all years of college is helpful in deciding which college to attend and in making sure that adequate savings are in place for a student to attend through degree completion.

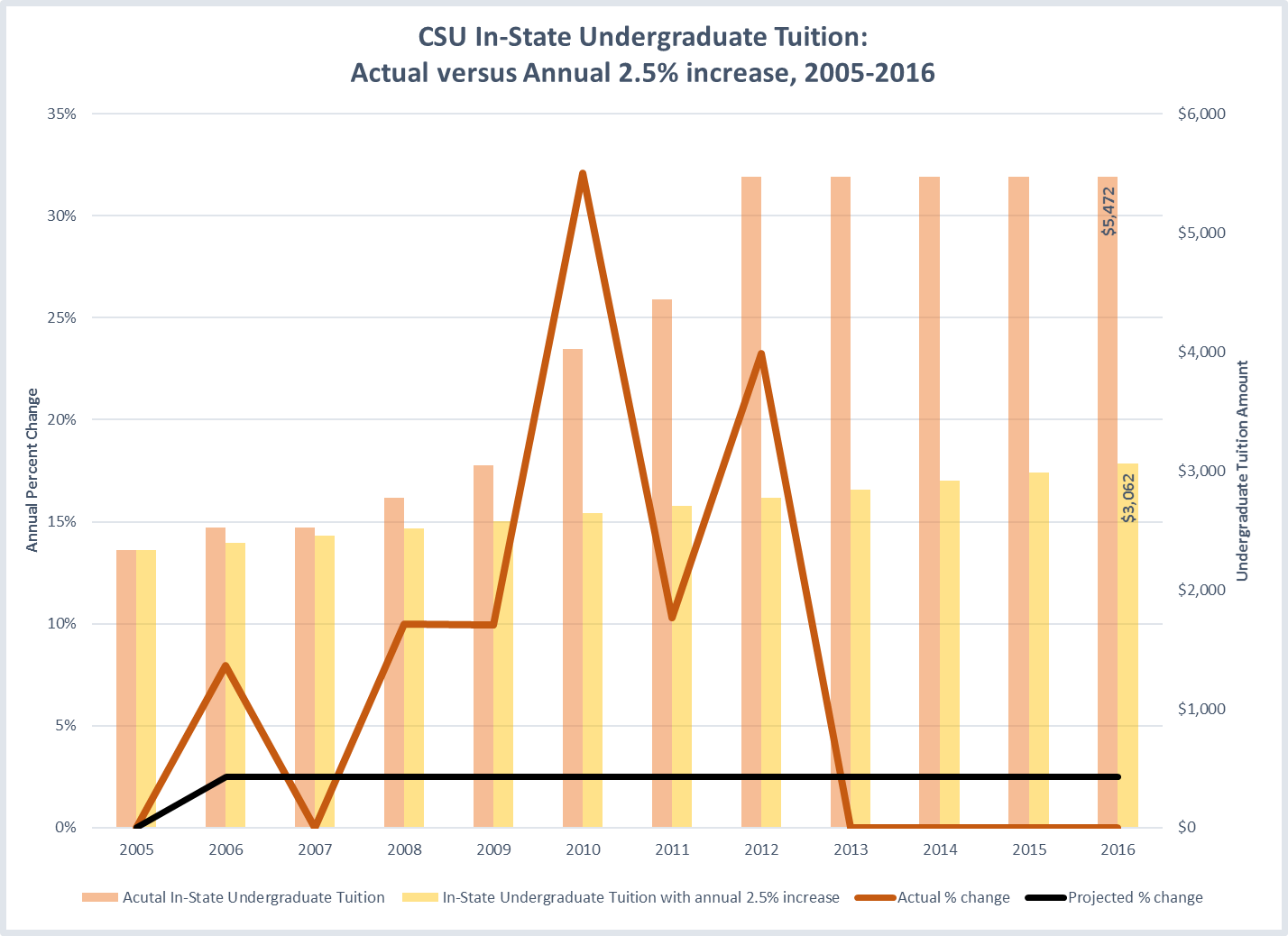

Prices in California have been especially volatile over the last decade. While prices increased on average by 4.5% per year from 1995 to 2005, between 2005 and 2016 price increased on average by 8.5% per year. Some year-to-year increases were even more dramatic: in 2010 price went up by 32%. Looking at changes in actual dollars is a further illustration of this volatility; on average from 2005-2016, prices went up by $285 per year, but in 2012 prices increased by over $1,000. Some students have made out well on this roller coaster ride: if you started CSU in 2012 then you paid the same amount in year one as in year four. However, for some unlucky students prices not only rose every year but even rose between Fall and Spring semesters: a student starting CSU in 2009 saw tuition increase 6 times from year one to year four including mid-year tuition increases in 2011. This means for those students that tuition was $2,424 more in year four than in year one (from $3,048 in 2009 to $5,472 in 2012 an 80% increase in four years). While it is true that the student who started in 2012 paid more overall in tuition over the four years, the student starting in 2009 had to come up with additional funds in each year, a hard pill to swallow. [1] While this example shows the volatility at the CSU, similar tuition spikes occurred at UC during this time period.

Tuition volatility, very simply, makes college harder to pay for and gives students and families little opportunity to come up with more money months before the semester begins. For students who could barely afford the cost of college the prior year, a large increase in tuition can leave them with a set of unattractive options. First, they could pay for the increased cost by taking out additional loans, if they find out about it in enough time to apply for more loan dollars. This means they will graduate with higher debt. Second, they could increase the number of hours they work. However, the more students work the less time they have to study, and increased work hours means students cannot take as many credits–meaning students may take longer to complete a degree (which also means an extra year of paying for tuition). Working more than 20 hours a week has been linked to lower degree completion. [2] Or third, if students simply cannot come up with the extra cash then they may decide to take a semester off. Stopping out of college not only slows momentum toward degree completion and delays a student’s entry into the workforce with a degree but has also been shown to increases the likelihood that the student will never complete a degree at all. [3]

All of these options are unattractive for students and families, but what is the alternative to tuition volatility? Some would argue for a return to free college—but, with state resources increasingly strained and cuts associated with the next economic recession simply a matter of when, not if, how long could the state afford to pick up the tab? Others would ask for institutions to improve efficiency so that there is less need for tuition increases. That argument has merit and there have certainly been efficiency efforts at both the UC and the CSU in recent years. However, it is unlikely that efficiency alone could generate enough savings to “buy out” tuition increases. State funding tends to vary from year to year because state revenues are also volatile, as they are built on the personal income tax base and tax revenues plummet during recessions.

So if we take it for granted that public higher education will need some additional revenues over the years, what is the alternative to the current spike/plateau cycle of tuition increases? The alternative is to build in a moderate, predictable and affordable annual tuition increase into the higher education budget. This would eliminate the inequity of charging certain students more and certain students less and would give the institutions a more reliable source of funding. Many would argue that this would lead to higher prices overall. However, if we look at the last decade we can see that is not the case.

The figure below illustrates the actual annual percent change in in-state undergraduate tuition and what the change would have looked like if tuition had increased by 2.5% per year from 2005 to 2016. Under the 2.5% scenario, the price in 2016 would have been $3,062 instead of the $5,472 actual price. But let’s look at what happens to tuition in year one and year four for the student starting in 2009 and the one starting in 2012. Instead of one paying the same over the four years while the other paid thousands more, both students experience moderate increases: the student starting in 2012 pays $288 more in year four than in year one and the student starting in 2009 pays $198 more. Both students see their tuition rise by less than $100 per year. Moreover, with a policy like this in place, the parents of a 9th grader could accurately predict what the cost will be at various institutions for their child four years later, helping ensure that they plan correctly for that cost.

Asking families to accept the idea of moderate tuition increases each year it may seem like a painful pill to swallow. However, the alternative of continuing this boom-bust cycle of tuition volatility is even harder on families. Making the cost of college predictable gives families, institutions, and the state ability to look ahead and plan responsibly. We end up with more graduates and institutions end up with a more reliable funding source. Planning for moderate tuition increases would help avoid these huge, unpredictable spikes in price, making higher education more affordable and accessible for everyone.

[1] Historic tuition and fee data from California Postsecondary Education Commission, and from California State University, Financial Aid and Tuition Rates.

[2] Will Doyle, “College Affordability: What the Research Says,” in College Affordability Diagnosis: National Report. (Philadelphia, PA: Institute for Research on Higher Education, Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania, 2016).

[3] A report from the National Student Clearinghouse demonstrates that completion is higher with students with zero stop-outs and that the number of completions declines as the number of stop-outs increases. D. Shapiro, A. Dundar, X. Yuan, A. Harrell, J. Wild, and M. Ziskin. Some College, No Degree: A National View of Students with Some College Enrollment, but No Completion. (Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, July 2014.)